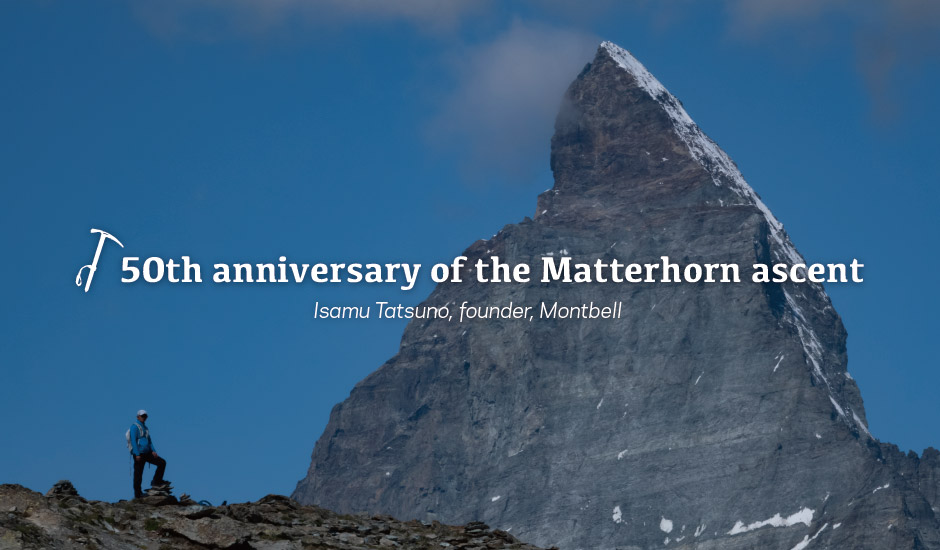

50th anniversary of the Matterhorn ascent

In 1969, I climbed the North Face of the Eiger and the North Face of Matterhorn at the age of 21. This year marks the 50th anniversary of those summits, which have had such an impact on my life.

In recent years, I have visited Switzerland every summer, looking up from the valley at these great peaks. Over the years, the desire to stand on top one more time has grown stronger. In particular, the magnificent dagger of the Matterhorn piercing the heavens has captivated me. Could I climb it again, in my 72nd year?

This age is significant for me, because my father passed away at 72. For a son, living beyond his father has a special feeling, like clearing a kind of hurdle. And challenging a big mountain at the same age adds to the pleasure.

Daniel Luggen, Director of the Zermatt Tourism Office, kindly offered to cooperate in this 50th anniversary climb. Benedikt Perren, the head of the Zermatt Mountain Guides Association, would share my rope, and his younger brother Andreas Perren would help Daniel film the climb.

In early July, 2019, Mayor Romy Biner-Hauser came to the Matterhorn Museum in Zermatt to commemorate the 50th anniversary of my climb.

Immediately after, I assembled my gear with Benedikt.

“Never forget a single item you need, but don't take a single item you don't,” he said, in the spirit of Light & Fast.

He said to leave behind the rain pants I had packed. “If you have to put them on, we’ve already made a mistake. For every single gram we shed from our load, we climb faster.”

I have worked to make Light & Fast the core concept of Montbell's product design, but I was surprised by his thoroughness.

The reason behind his approach is the recent improvement in weather forecasting. If bad weather is coming, don’t climb. Go instead when clear skies are certain. In other words, there is no need to pack excessive equipment in case of bad weather.

Acclimatization on the Breithorn

At Daniel's suggestion, I decided to climb the Breithorn (4,164 m) in preparation for the Matterhorn, in order to acclimatize to the altitude.

From Zermatt, we took the cable car to the Matterhorn glacier paradise (3,883 m), from which it is a 281 m ascent on snow to the summit. It is considered a relatively moderate trail for the Alps.

When I exited the cable car onto the glacier, I could see the trail to the summit and nearby skiers enjoying the summer snow. After descending the gentle slope to the icefield, I roped up with Daniel and began to climb in his footsteps. Although the route presented little technical difficulty, the air over 4,000m is thin and difficult to breathe.

I had caught a bit of a cough before leaving Japan, and my physical condition was not perfect, and soon I began to feel the symptoms of altitude sickness. There is no specific medicine for altitude sickness. You just have to consciously breathe a lot even to take in just two-thirds of the air you get at sea level. Slowly, we advanced across the snowy surface in our crampons.

On the way, we crossed two small crevasses, but they posed no great problem. We reached the snowy ridge after about two hours. Unlike the dome-shaped form the mountain presents from Zermatt, the top was an arete, or knife-edge. From the summit, the panorama opened in front of me, and the magnificent Matterhorn towered above.

To the Matterhorn

On the afternoon of July 10, the day after climbing the Breithorn, I trekked with Daniel to the Hörnli Hut (3,260 m), the base for climbing the Matterhorn. The Hut, which was renovated two years ago, is now so comfortable that it is hard to believe it is a mountain hut. I even had an en suite bathroom. The employees at the Hut wear Montbell jackets as their uniform, thanks to the manager Edith Lehner.

In the evening, Benedict and Andreas joined me over dinner to discuss the following day’s climb.

I was in poor condition after the Breithorn and had no appetite. It was all I could do to force down a little soup. Benedict suggested that we should leave last the next morning. This way, we could set our own pace without worrying about the other parties behind us.

On July 11, only about seven groups were climbing the Matterhorn. We set out in the dark at 4:00am and scrambled up the rocky ground by the light of our headlamps. I was next after Benedict at the front, immediately followed by Andreas leading Daniel.

Fixed ropes were secured at key uphill points as a kind of via ferrata, but I am not good at pulling myself up a rope hand over hand, so instead I looked for holds and climbed making sure I had three points of contact on the wall. People generally have much stronger legs than arms and climbing by pulling yourself up a fixed rope requires very strong arms.

Meanwhile, my altitude sickness was getting worse.

To continue climbing or to descend?

Guides move at a measured speed, to ensure that a climb finishes on time, but my movements were sluggish. When the sun finally came up and lit the rock wall, we had not even reached halfway. We took a break a little further on, just beyond the Solvay Hut (used for emergencies). By now, we were just beyond the midpoint.

A Japanese group that we had overtaken on the way caught up as we rested. Before continuing, they eyed us suspiciously and said, “We heard that the guides don’t allow you to take breaks, but I guess you can, right?!”

In general, it seems that one is not supposed to take breaks on a guided climb. In this case, the reason why Benedict decided to stop temporarily was because of my poor speed. We held a meeting to discuss whether we should go on or turn around.

“We’ve only reached a quarter of the way. It’s difficult to continue like this,” began Andreas. Of course, halfway to the top is only a quarter of the total distance back to the bottom.

If I couldn't climb according to the schedule, the only option was to go down.

“I will follow your decision,” I answered.

To this, Daniel said, “Continuing is still an option.”

Benedict hesitated.

"What time is it?" I asked, to which Benedict answered, "It's 8:00 am."

I was torn. We had already passed the Solvay Hut, we were more than halfway, and the weather was fine. In my experience, deciding to return at 8:00 am in good weather was a first. Still, I decided that I would respect and follow whatever they decided.

"I’ll respect your judgment,” I said, but gazed longingly at the summit.

Daniel understood my feelings well.

"Tatsuno, do you want to see the summit?"

“Oh, absolutely.”

“Then let's continue!”

Benedict nodded in agreement while Andreas reluctantly concurred.

Despite my fragile and altitude-sick body, my willpower and desire to climb was unwavering, “Alright, let’s continue then.”

We resumed.

Eventually we arrived at a point called the Shoulder. The skill required for this section was certainly not advanced. However, altitude sickness continued to hinder my movements. I climbed step by step, mechanically grabbing holds and seeking purchase with my feet.

At the summit for the first time in 50 years

Fifty years ago, I bivouacked three-quarters of the way up the North Face of the Matterhorn with Sanji Nakatani. The next morning, we reached the summit, descended the Hornli Ridge and hurried all the way down to Zermatt without using the cable car.

Earlier that summer, we had made the fastest ascent of the North Face of the Eiger for our age, and we used the momentum of this achievement to catapult ourselves up the North Face of the Matterhorn. As 21-year-olds, our hearts brimmed with confidence and unlimited possibility. Now however, I was a sad sight staggering up the same route I had descended with such strength.

We put on our crampons 200 m below the summit. Good balance and a strong core are even more necessary to climb a rocky ridge with crampons.

My mental sharpness was fading from the altitude, but I felt no fear, and just calmly continued to do what was required of me. Eventually, the view opened up, as we emerged onto a snowy ridge. I painstakingly made my way along the narrow ridge, barely a meter wide, and stood on the summit at last. It was 11:05 am.

“Congratulations! Well done!” enthused Benedict, gripping my shoulder.

"Look, the North Face you climbed 50 years ago!"

Looking down, the legendary face stretched 1,500m down to the Zmutt Valley.

Daniel murmured, “50 years ago…”

Yes, this was unmistakably the view I had had five decades earlier. It now seemed like yesterday.

Daniel, Benedict, Andreas -- thanks to you, I was once again able to stand on top of the Matterhorn.

For a moment I sat down on the summit and gazed out over the mountains above the clouds.

“Thank you.” The gratitude I felt then was for everyone that has supported me in this life.

Equipment for the Matterhorn

1. Dyna Action Parka, 2. Kajita Ice Ax, 3. L.W.Alpine Helmet, 4.Trango Gravity, 5. Altiplano Pack 20, 6. Alpine Folding Pole, 7. Kajitax LXB-12 Crampons, 8. Asolo Eiger XT GV, 9. Merinowool Supportec Trekking Socks, 10. Supportec Tights, 11. Cliff Light Pants, 12. Climapro Watch Cap, 13. Zeo-Line L.W.Balaclava, 14. Cyclimb Jacket, 15. Belay Gloves, 16. Merinowool Glove Touch, 17. Ignis Down Parka, 18. O.D.Roll Paper Kit

ISAMU TATSUNO

The story of Montbell is the story of its founder and CEO, Isamu Tatsuno. Born in 1947 in Osaka, Japan, Tatsuno spent much of his youth dedicated to becoming a mountaineer. Deeply impressed by "Heinrich Harrer's White Spider: The Classic Account of the Ascent of the Eiger", Tatsuno had two dreams; to be the first Japanese person to climb the North Face of the Eiger and to start a company somehow involved with the mountaineering industry.

By the early 1970s, Tatsuno had achieved his first dream by becoming a renowned climber. In 1969 at the age of 21, he became the second Japanese to climb the North Face of the Eiger in the Swiss Alps. He also climbed the North Face of the Matterhorn. In 1970, he opened the first rock climbing school in Japan.

In 1975, when he was 28 years old, Tatsuno achieved his second dream when he founded his own company, Montbell Co., Ltd., to manufacture mountaineering clothing and equipment.